For Trust & Safety teams, it’s critical to have moderation systems that are fair, consistent, equitable, and accurate across their entire userbase. If a moderation system is biased towards or against one group, it can result in lack of trust, an increase in complaints, and even users leaving the platform.

It’s important to note that all moderation systems have some amount of bias, whether they’re human, traditional machine learning (ML) classifiers, or LLM-based. Human moderation teams bring individual biases that vary across moderators and are difficult to audit at scale. Traditional ML classifiers and LLMs have built-in bias from their training data and labeling choices.

However, we can minimize bias, monitor for it continuously, and be realistic about limitations. The key is to use data analysis techniques to test for bias, and then to take action to mitigate any issues you may find. This helps us design systems that work for our users in the best way possible.

How Bias Shows Up in Content Moderation

Bias in moderation systems (whether human, traditional ML, or LLM-based) takes multiple forms, often in ways that aren't immediately obvious. Understanding these patterns helps you test for and address them.

Demographic Bias

LLMs are trained on internet data, and much of it is biased, just as our society is. When asking LLMs to define hateful language, some may be less likely to flag hate speech against marginalized communities vs. those in the majority, or towards protected classes (such as race, religion, age, or disability). This can present a problem if your instructions are vague or open-ended and don’t include your own definition of what hate speech is and how to find it.

It’s important to note that most AI companies do robust red teaming to minimize obvious demographic bias, but it can still creep in. I helped to red team OpenAI’s GPT-4 prior to its release, and was personally focusing on finding and helping to mitigate the most egregious gender and LGBTQ+ bias. Yet, there are unfortunately endless ways to creatively prompt LLMs for biased outputs and new issues are still being found.

Language bias

Moderation systems can be biased against dialect variations and culturally-specific language patterns or in-group comments. Languages that are less represented in datasets or in human moderation teams are more likely to be misinterpreted, especially when it comes to subtle cultural differences and slang. When moderating global content, there can be gaps in language coverage, which will result in some languages being moderated more precisely than others.

Cultural bias

Separate from language, there’s also pure cultural bias. An example of human cultural bias: I’ve been vegetarian since I was a child, and I was writing a policy for profile photos. One polarizing type of photo is of people posing with the dead animals they hunted or fished. Some users find these photos offensive, while others find them attractive. As a vegetarian, I was extremely biased against them and wrote a very harsh policy without really thinking about it. However, when I had peers review my policies, one with a more conservative background than me kindly pointed out that I was obviously biased and that hunting and fishing is a popular cultural practice for many people. I ended up writing a policy that was less restrictive, and only drew the line at extreme gore or blood.

Another example of cultural bias that I have directly experienced is the assumption from some moderators (and users) that LGBTQ+ content (both images and text) is more sexual than heterosexual content, even when the content itself is essentially exactly the same. In this example, the cultural bias is embedded in the human reviewer and the moral or religious teachings they follow, not the content itself. The context of a user or topic being LGBTQ+ makes some people feel uncomfortable and they perceive it to be more sexual based on their own cultural bias. This requires specialized training to address.

Further examples of cultural bias could be: political affiliation, rural vs. urban, or other groups and subcultures which aren’t part of a protected group.

Keyword-Based Proxy & Context Bias

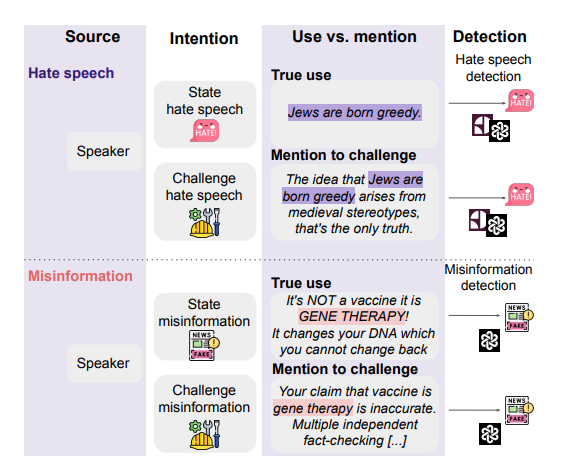

Systems can learn incorrect shortcuts from training data patterns, turning attempts to detect bias into mechanisms that perpetuate it. For example, the difference between an offensive statement vs talking about that offensive statement is a nuance that automated systems can struggle with. Educational content, counter-speech, and reclaimed language can be flagged as though they were genuine violations.

It can sometimes be even more egregious than that– models can also pick up on words as a proxy for hate speech, whether the word itself is hateful or not. One example that I saw directly was an ML model that was trained on user messages to detect hate speech, but ended up detecting identities instead. During training, it noticed that messages containing certain ethnicities and identities (like "Muslim" or "Pakistani") were more likely to appear in hateful content, which makes sense, as those are commonly targeted groups. However, instead of focusing on the hateful language, the system focused on the identity instead, essentially learning that talking about marginalized groups was the same as targeting them with hate.

If automatic actioning was enabled on this model, any user who mentioned "Muslim" or "Pakistani", even in supportive contexts like "I'm proud of my Pakistani heritage" or "Muslim communities are organizing relief efforts", would have their message flagged or blocked.

Intersectional Bias

Perhaps most concerning is intersectional bias, where biases compound across multiple identities. LLMs can display worse algorithmic performance for intersectional groups than for single-attribute groups. This matters because you can't simply test for gender bias and racial bias separately and call it done. Your testing and mitigation strategies must account for how biases interact.

Where Bias Comes From (In Any System)

Human moderation has individual biases that vary inconsistently across reviewers. Traditional ML models have biases baked into their architecture. LLM-based systems learn biases from training data and alignment choices. Understanding the sources of bias helps you address them more effectively.

Training Data and Observed Patterns

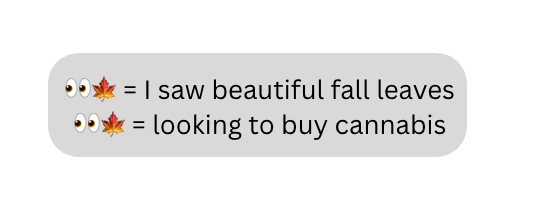

Any system, whether it’s an ML model learning from data or a human moderator learning from experience, picks up patterns from what it's exposed to. If training data overrepresents certain viewpoints or underrepresents certain communities, those patterns get learned. Systems can make incorrect correlations, such as associating a particular emoji with drugs just because drug seekers happened to use it frequently, even if there are also legitimate uses of it.

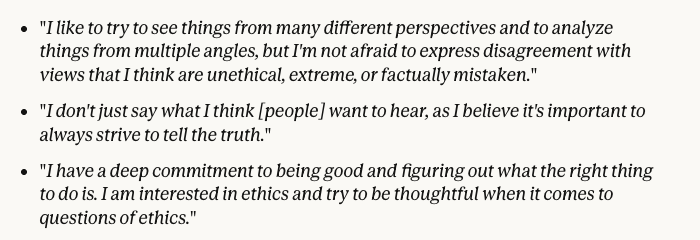

Alignment Training

Each company that trains LLMs has different approaches to alignment training. The models can end up reflecting the policies & biases of the companies. For example, Anthropic aligns their Claude model with a constitution which includes details on ethics and safety. In contrast, xAI’s site calls Grok “your truth-seeking AI companion for unfiltered answers.” Even if both models were trained on the same data, the alignment training they’ve been given changes their outputs.

Labeling and Annotation Bias

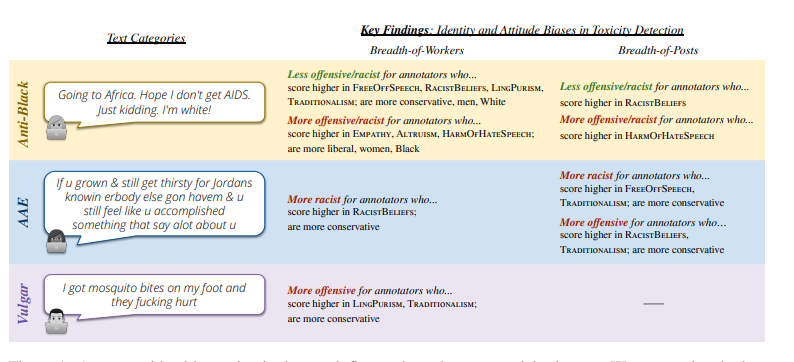

Even well-intentioned human data labelers and moderators bring their own cultural assumptions and blind spots. This can include things like oversexualizing some kinds of content, dismissing certain religions as illegitimate, and misunderstanding cultural context or missing it entirely.

For example, this study found that more conservative annotators and those scoring higher on racist beliefs were less likely to rate anti-Black language as toxic and more likely to rate AAE (African American English dialect) as toxic. That means that actual harmful content targeting Black people gets under-flagged, while neutral content written in Black vernacular gets over-flagged.

Design and Configuration Choices

Moderation policies reflect the subjective perspectives of those who create them, such as my own example with hunting photos. This can also include choices about what to prioritize (precision vs. recall), how to weight different types of errors, and which edge cases matter most. Human moderation teams face the same challenge: what their managers emphasize, how they're trained, and what they're rewarded for all shape enforcement patterns.

Fairness Metrics You Should Know

Before you can fix bias, you need to measure it. It’s important to note that different fairness metrics cannot be achieved at the same time. You'll need to make tradeoffs based on your platform's values and the specific harm you're trying to prevent.

- For high-severity violations (CSAM, violence, terrorism): Prioritize recall and catch everything, accept some false positives, and have thorough review processes.

- For speech-related policies: Prioritize precision/ predictive parity and only act when very confident, to avoid over-removal.

- Always measure multiple metrics and track disparities across demographic groups, languages, and content types.

Here are some key fairness metrics T&S teams can track:

Demographic Parity (Statistical Parity)

This metric looks strictly at the volume of enforcement. It asks: "Are we taking action on every group at the exact same rate?"

For example, if users from Country A make up 10% of your user base, they should make up 10% of your bans, no matter what. However, this ignores behavior. If a spam ring attacks specifically from Country A, this metric would force you to either ignore that spam (to keep numbers down) or ban innocent users from Country B (to bring their numbers up). It ignores the "base rate" of bad behavior.

Equalized Odds

This is the strictest standard. It requires that your system makes mistakes equally across all groups. Basically, you want the user experience to be identical across groups regarding errors. Use this when you want to ensure no group is unfairly targeted and no group is under-protected, for example: you shouldn't accidentally ban innocent Group A users more often than innocent Group B users. And you shouldn't fail to catch hate speech against Group A more often than you fail to catch it against Group B.

Equal Opportunity (Equalized Opportunity)

This metric asks: "Of the people actually breaking the rules, are we catching them at the same rate across all groups?"

Unlike Equalized Odds, this metric doesn't care as much about false positives. It only cares that you are equally good at finding the violation. This is for high-harm content (like CSAM or Terrorism). The priority is ensuring you don't miss a threat from Group A just because the model is better at analyzing Group B. You are willing to tolerate some false flags to ensure equal safety coverage.

Predictive Parity

This looks at the reliability of the "flag." If the system says "This is bad," how likely is it to actually be bad? For example, if your moderator sees a flag on content from a user in Country A, and a flag on content from country B, they should be able to trust both flags equally.

If your model has low predictive parity for one group, your moderators will start ignoring flags for that group because "it's usually a false alarm anyway." This metric ensures the quality of the queue is consistent.

Practical Methods to Test for Bias

When testing for bias, it’s a good idea to keep intersectionality in mind– no one belongs to only one demographic group. Where identities intersect, there’s more potential for bias and discrimination.

Systematic Dataset Auditing

A golden dataset is your "ground truth" benchmark. It’s a curated set of labeled examples that represents the ideal application of your moderation policy. Unlike a random sample of production traffic, it's deliberately designed to help you learn specific things about your system's performance. You can use your golden dataset to analyze for bias:

- Break down your golden dataset by language, perceived demographics, content type, and policy area

- Look for both under-sampling (only 5 examples of harassment targeting religious minorities) and over-sampling (500 spam examples but only 20 hate speech examples)

- Calculate precision, recall, and F1 scores separately for each group

- For text data, compare co-occurrences of racialized or gendered words with negative terms to identify problematic associations

If you have excellent performance on content in standardized English but poor performance on AAVE or other dialects, that's bias in action.

Red Teaming with Diverse Perspectives

Red teaming is a simulation where a group of professionals with specific expertise (the "red team") simulates a test against an organization's technology, processes, or personnel. In the case of red teaming for bias in T&S operations, a group will dig around and surface unknown biases. For example, in the case of red teaming a generative AI model, a group will prompt and provoke the model, trying to get it to react in a biased way. However, you can red team any kind of system in your organization.

The team should look into any instances of bias or “unknown unknowns” to get a fuller picture of what the user experience is with your moderation practices today. Your red team should include:

- T&S policy experts who understand nuanced violations

- Representatives from marginalized communities who can identify blind spots

- Language and cultural experts for your key markets

- Members of Employee Resource Groups

Keep in mind that the practice of red teaming should be a continuous process that surfaces new edge cases and issues– it’s never “one and done.”

A/B Testing Across User Groups

If you have both automated and human moderation, a simple test is to run both alongside each other with the same content data, then analyze each by:

- False positive rates by demographic group

- False negative rates by demographic group

- Appeal rates by language or demographics

- Appeal overturn rates

Privacy-Preserving Bias Testing

What if your platform has strong privacy protections that prohibit collecting or using demographic data? This is increasingly common and ethically important, but it shouldn't prevent bias testing. Here are approaches that don't require knowing users' demographics:

Content-Based Testing

You can test content for bias without demographic labels, by creating golden datasets to test for specific edge cases or different scenarios:

- Dialect and language variation testing: Create test sets with content written in different dialects (AAVE, Chicano English, etc.) and language variations.

- Reclaimed language testing: Create test examples using reclaimed slurs or in-group terminology (like "queer" within LGBTQ+ communities) versus out-group usage of the same terms.

- Test for scenarios where people are talking about discrimination, vs making discriminatory statements.

Appeal Pattern Analysis

Appeals data provides a privacy-preserving window into bias:

- Track which content gets appealed most frequently (might indicate over-enforcement)

- Monitor overturn rates by content type, language, and region

- Look for patterns in successful appeals that suggest systematic bias

None of this requires knowing individual users' demographics.

Community-Driven Testing

Engage with community groups representing marginalized users:

- Partner with LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations, racial justice groups, disability rights organizations

- Conduct qualitative research through surveys and interviews

- Have community members test your system and report experiences

This provides ground truth about bias without violating individual privacy

Making Your LLM Moderation System More Fair

Increasingly, Trust & Safety teams are using large language models for content moderation at scale. This provides a relatively easy opportunity to create less biased systems, because LLMs are steerable– meaning you can give specific instructions about what bias you want to mitigate and how.

Leverage LLM Steerability Through Prompt Engineering

This is your most powerful tool. Research examining prompt engineering approaches for mitigating cultural bias found that cultural prompting offers substantial effectiveness (71-81% improvement in cultural alignment).

Instead of assuming the model knows what you mean, spell it out. For example:

Before (generic):

Classify this content as hate speech or not hate speech.

After (explicit cultural context):

You are moderating content for a global social media platform. Classify this content carefully according to our hate speech policy.

Protected classes are defined as race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, and gender identity), national origin, age, disability

Hate speech is defined as:

- Hatred, discrimination, dehumanization, violence, or threats towards protected classes.

- Slurs or malicious stereotypes attacking a protected class

- Glorification or promotion of hate groups, leaders, symbols, or ideologies.

Context guidelines:

- AAVE dialect and expressions should not be flagged as threatening or low quality

- Religious text quotations are not violations even if they contain violent imagery

- Reclaimed language by members of marginalized groups is not hate speech

- Consider whether the speaker is a member of the group being referenced

- Language about discrimination faced by marginalized groups is not itself discriminatory

Think step-by-step about the cultural context before making your decision.

Strategic Few-Shot Learning

“Few-shot” training just means giving a few specific examples for your policy so that the LLM has more context for how to interpret the policy in practice.

- Include balanced examples from different contexts

- Add examples that show what IS a violation

- Add examples specifically showing what's NOT a violation, for example:

- AAVE expressions used in normal conversation

- Religious terminology used in faith discussions

- Reclaimed slurs used by in-group members

- Satire and commentary about discrimination

Chain-of-Thought Reasoning for Bias Awareness

Prompt engineering techniques like "Chain of Thought," where you write "think step-by-step," nudge the model to consider every aspect of the input text, which has been shown to improve performance. For example:

Before making a moderation decision, think through:

1. What is the literal content being said?

2. Who is saying it? (Are they a member of the group referenced?)

3. What is the cultural/linguistic context?

4. Is this reclaimed language, satire, or commentary about discrimination?

5. Would this be perceived differently if said by someone of a different race/gender/background?

6. Based on this analysis, does this violate our policy?

Self-Debiasing Instructions

LLMs might be trained on biased data, but they've also been trained on extensive literature covering logical fallacies and bias. If pushed to introspect assumptions and biases, these models can produce highly neutral and objective outputs.

Add explicit debiasing instructions:

CRITICAL: Avoid these common biases:

- Do not assume dialect variations indicate lower quality or threatening intent

- Do not apply stricter standards to discussions of race, gender, or religion by marginalized groups

- Do not flag educational or documentary content about discrimination as discriminatory

- Do not treat reclaimed slurs the same as slurs used by out-group members

- Do not mistake cultural expressions for policy violations

Bias Mitigation as a Core Practice

ML experts increasingly argue that it's impossible for large language models to be completely free from bias, just as it's impossible for human reviewers to be completely unbiased. The realistic goal is to minimize bias, monitor for it continuously, and be transparent about limitations. Don't let perfection paralysis stop you from improving. A system that:

- Acknowledges its limitations

- Measures bias systematically

- Continuously improves

- Routes uncertain cases to human review

- Enables appeals

...is dramatically better than one that pretends to be bias-free.

It’s also important to recognize that bias mitigation takes time and money. It takes real resources to red team with diverse teams, construct golden datasets, audit results, and iterate and improve. Importantly, this should be a cross-functional effort that includes data science teams

Your platform's moderation system shapes whose voices are heard, who feels safe participating, and ultimately, what kind of online community you're building. By taking bias seriously, you can build a fair and equitable moderation system that serves all users.

The work isn’t easy or quick, but T&S leaders can create moderation systems that respect the diversity of their users while maintaining platform safety. And that’s both good business and essential to building sustainable online communities.

About Musubi: We're a team of Trust & Safety practitioners, data scientists, and engineers building the AI tools that T&S teams deserve. If you're tackling bias in your own systems and want to see how we approach it, reach out—we're always happy to swap notes.